With the clutch removed, the process of getting off the clutch housing proved to be involved enough that I will make it yet another separate post. Truthfully, removing the starter, clutch, flywheel, and clutch housing, and then mounting the motor to an engine stand were all accomplished in a single long day, but I need to talk this through and document it for my own benefit as well as either of my readers, so a separate post it is.

Here (above) is the flywheel in place, with the bolts for the clutch replaced (so I don’t lose them). Below, the three groups of paired bolts holding the flywheel to the crankshaft are visible. The metal straps through which they are bolted are anti-unbolting devices. Each corner of the strap is folded up beside each bolt head, making a tab that keeps the bolt from turning. As you can see below, I used a cold chisel (and should have used a drift punch) to tap the corners/tabs down flat so the bolts can be unscrewed.

With the mounting bolts removed, the flywheel simply had to be tapped gently from the end of the crankshaft. There is no room at all inside the clutch housing, so that was most easily accomplished through the hole left by removal of the starter motor. Fortunately I have a piece of leftover hickory that worked perfectly: some light taps on the hickory, turn the flywheel (and crank), s’more light taps, and eventually the flywheel moved back far enough on the crank that I could pull it manually.

Once loosened, the flywheel simply lifted off and was filed as well.

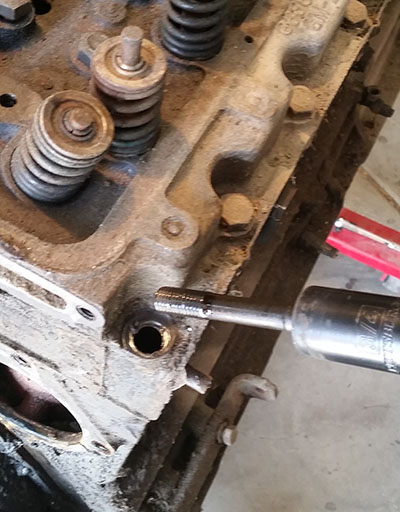

Removing the flywheel finally gave me access to the internal mounting bolts attaching the clutch housing to the engine block. As you can see, this was not a minor deal. There are four bolts, and inside the dark recesses of the housing, they were hard to spot beneath the accumulated grease, dust, animal hair, leaves, straw, sticks, etc. They were easily removed, however. Remember, the clutch housing is not exactly hermetically sealed. A few smacks with the hammer loosened the housing and it simply lifted off

Curiously, the clutch housing has a port at the top, covered by a plate. On Green the plate had only a single screw, but I think I found the other earlier in the action. That thing that looks like a handle, running across the top of the housing, is the linkage from the starter pedal to the motor. Remember, Green is of an age that it has a kick-starter rather than an electric start. It makes a convenient handle for the chunk of metal that is the housing. The picture, below, was taken before removing the housing, but you get the message.

At this point the engine was mounted to the stand as described in the earlier post, and I disassembled the hoist, shoving it to one side.

Now the motor comes apart.